If you’ve been enjoying the Deaf History Series on Twitter, I’m going forward, episodes will also be posted here, rather than on Threadreader, as the app monetizes off the work of writers without credit.

Welcome back to another episode of #DeafHistorySeries! This week’s feature is Cuban-American Emerson Romero (1900-1972), a silent film actor known by his stage name Tommy Albert, and innovator of deaf technologies, including film captioning.

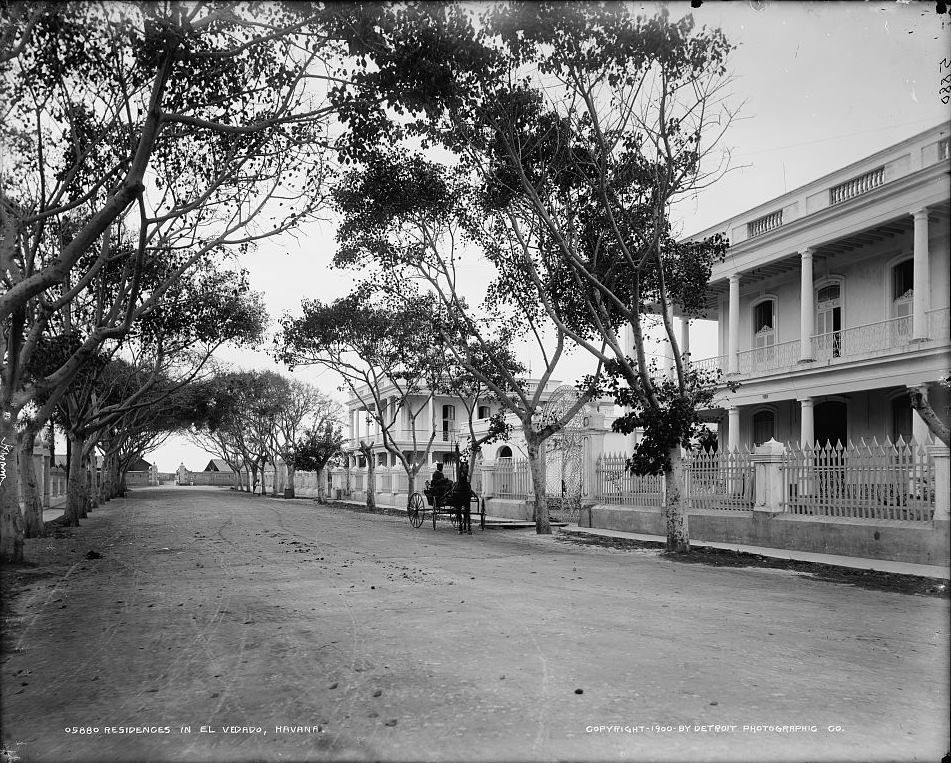

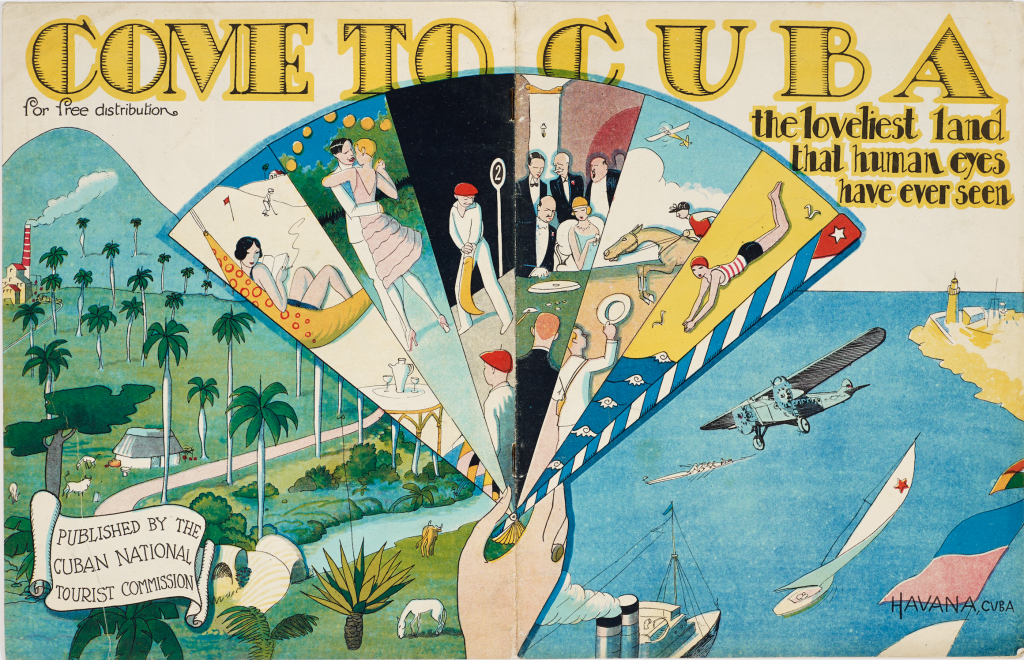

“Ever since I was a kid I wanted to act in pictures.” Emerson Romero was born on 19 August 1900 in Havana, Cuba, to a wealthy family who exported sugar to the United States, second of 3 sons.

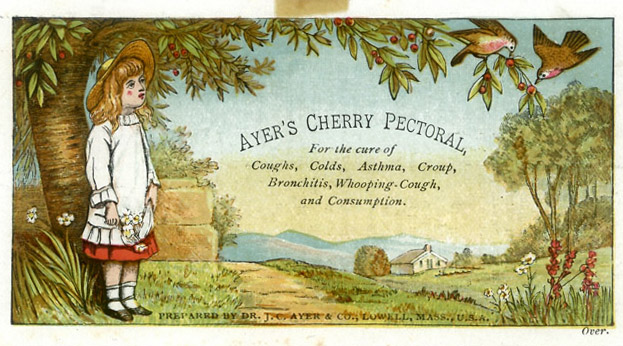

At six years old, Romero became ill with whooping cough, a highly contagious respiratory infection. The disease results in long-term complications, including irreversible hearing loss. Romero thus was completely deaf.

Learn more about whooping cough

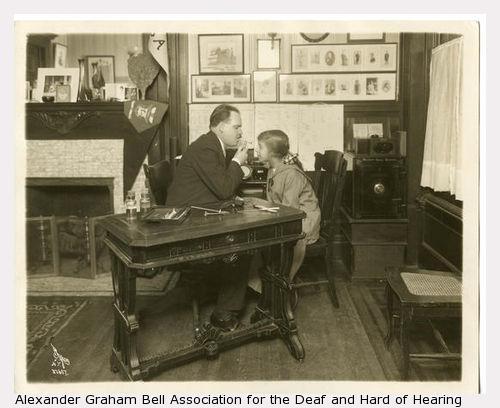

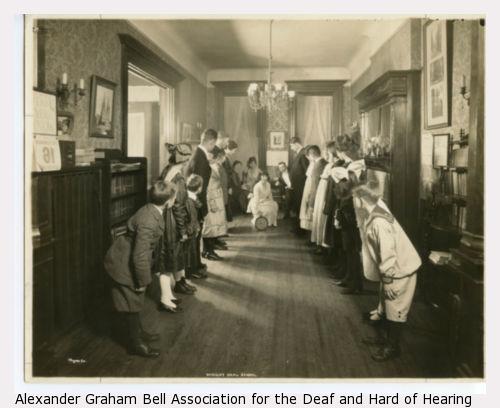

Wanting their child to receive a proper education, the Romeros sent their son to New York City to the Wright Oral School, which opened in 1902. Founded by John Dutton Wright (1866-1952), the school focused on teaching deaf children speech. Helen Keller was one of the pupils.

Romero resided at the Wright Oral School from 1907 to 1915. He received good command of spoken and written English through speech reading. He even learned finger spelling and rudimentary sign language—likely from his classmates—and retained his original Spanish.

He then attended mainstream high schools in New York, Indiana, and New Jersey. It’s not clear why Romero relocated frequently. He graduated in 1920. His high school years were enhanced by athletics, especially basketball and boxing—he even won several boxing championships.

After graduation, Romero enrolled into Columbia University to study engineering, before transferring to Lafayette College in Pennsylvania. He left school after his father encountered financial difficulties, staying in New York City and working at the Federal Reserve Bank.

Romero stayed in NYC until 1924 when his brother Dorian came to retrieve him to Cuba to work in his company as a silent film actor: “My elder brother was the first to realize that I had an acting ability. He had been saying for years that he would put me in pictures.”

Dorian formed his own film company, the Pan-American Film Corporation, which produced films for the Cuban government to promote tourism. He felt Emerson’s skilled movement, facial expressions, and athletic ability would make him a natural actor.

Emerson Romero’s first feature film was a 6-reel comedy that Dorian wrote, “A Yankee in Havana.” The film was a commercial failure but Romero’s talents were noticed by director Richard Harlan, who then contracted the actor to make several films with him.

Silent films were immensely popular with both hearing and deaf audiences. Deaf people in particular, could participate as equal members—as audience, actors, and subjects. They enjoyed these films for the action and actors’ expert use of facial and body expressions.

To succeed, Romero was advised to change his name, as it was suitable for a romantic lead, but not comedy. “Our distributors wanted my name changed to one more American-like; one that could be easily remembered, pronounced, and spelled correctly.” He became “Tommy Albert.”

In the late 1920s, Romero was one of five deaf actors working in the industry. Typical of small production companies, he also edited the reel, wrote and corrected scripts, and wrote the texts introduced between scenes.

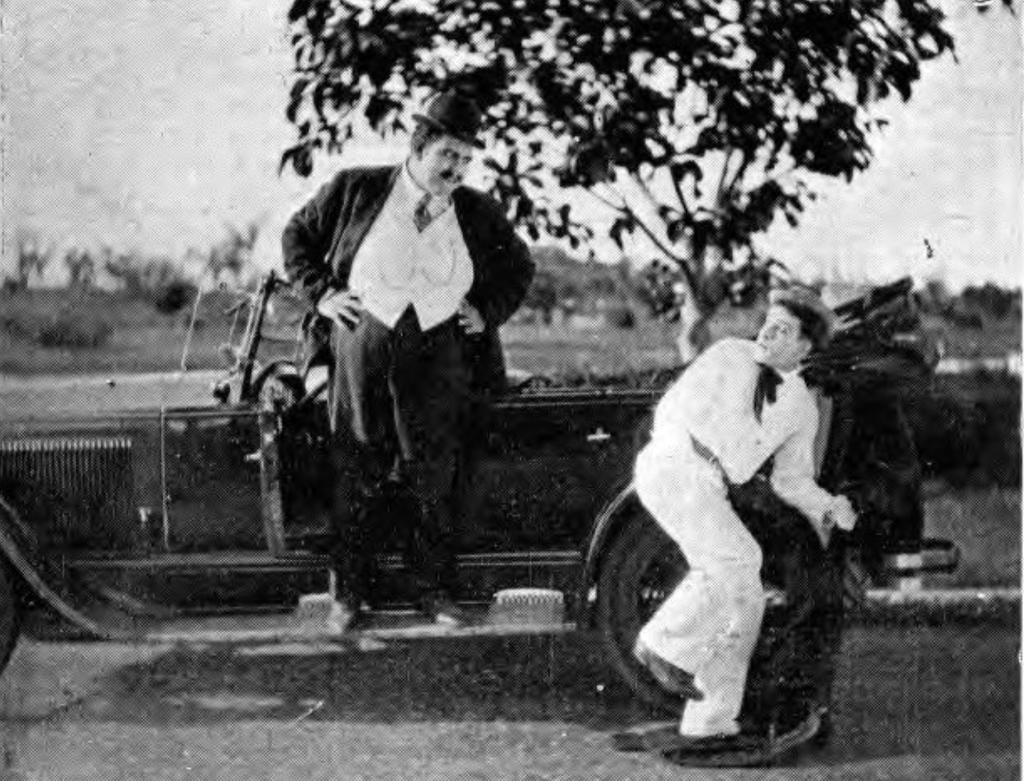

In 1926, Romero starred in more than 24 two-reel comedies, including: “The Cat’s Meow,” “Sappy Days,” “Great Guns,” “Hen-Pecked in Morocco.” He also studied Charlie Chaplin’s technique & worked with other stars: W.C. Fields, Janet Gaynor, & deaf actor Granville Redmond.

Working on set required accommodations. Everything was done in English so Romero trained himself to synchronize his acting with tempo of the cameraman’s cranking: “I watch him all the time and I can tell, by the way he moves his hand, when is the right moment to start acting.”

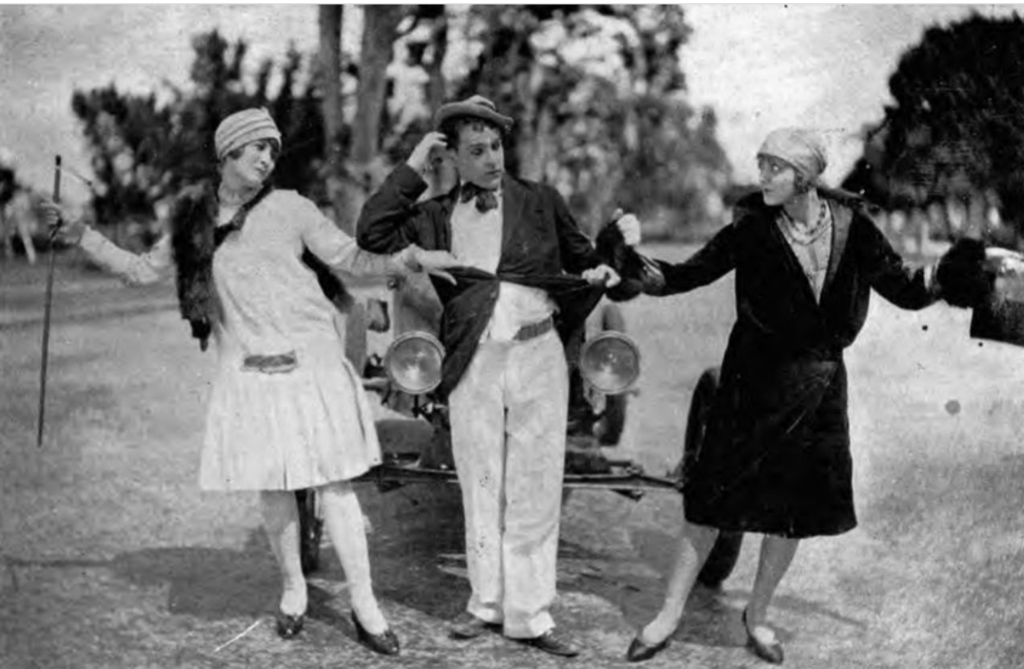

For his film “Great Guns” (1926), Romero convinced the producers to hire Cuban deaf-mute actress Carmen de Arcos (pic), who he met through a mutual friend. On set Romero communicated with de Acros via signs and finger spelling. They acted in three films together.

Emerson Romero’s acting career ended in 1929 when “talkies” were introduced. The new means of access for the hearing audience made text on screen redundant and excluded deaf people. Silent films, however, were still shown in deaf schools and clubs.

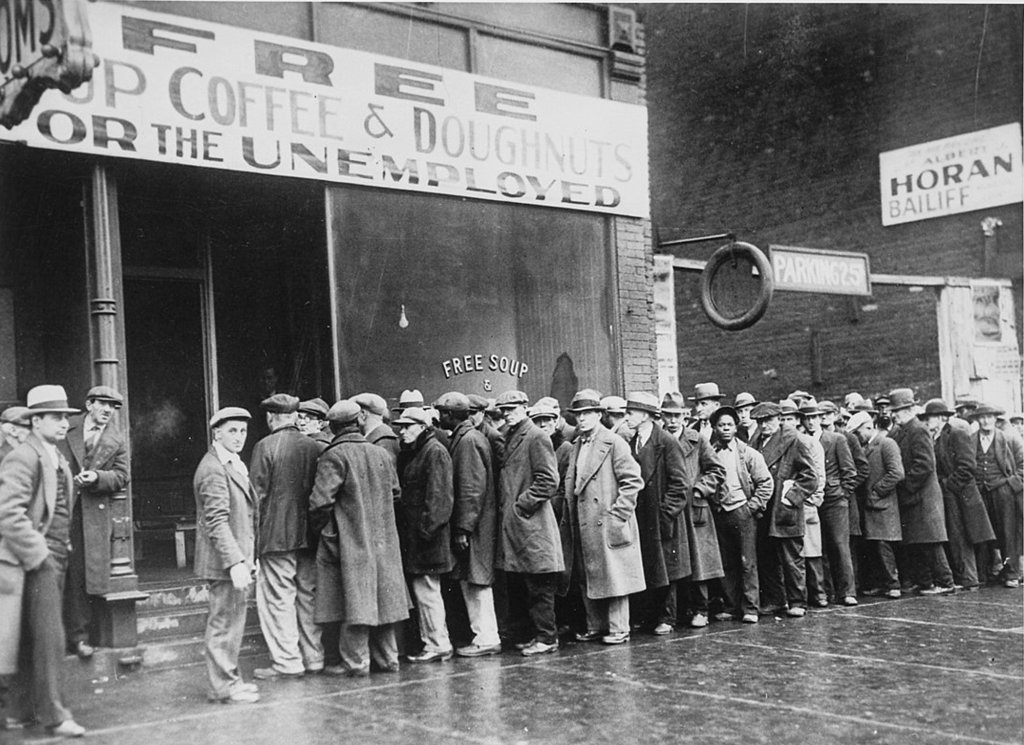

During the Depression years, Romero worked as a bank analyst in New York. Dorian had tragically died at age 32, which also ended the family’s film company. Though Romero was previously briefly married & divorced (maybe to Carmen de Arcos?), in 1936 he married Emma Corneliussen.

Along with Sam Block and John Funk, in 1934 Romero established the Theatre Guild of the Deaf. The goal of the Guild was “to own a theatre for the deaf to be used as a social center and show house and to entertain both the deaf and the hearing.” Romero directed 20+ deaf actors.

During WWII, Romero shifted careers and worked as a sheet metal and template company for Republic Aviation Corporation. The company produced P-47 fighter planes for the war effort. Romero remained with the company until his retirement in 1965.

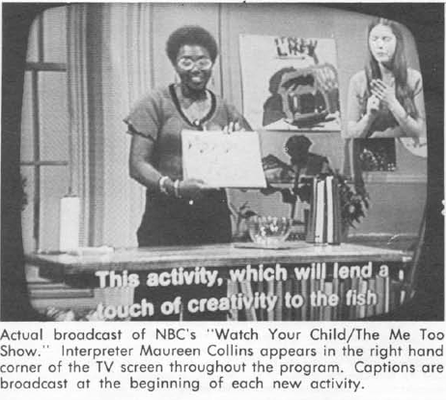

Guided by his own experiences at a production company and wanting to improve accessibility, in 1947 Emerson Romero spent his own money to create a captioned movie library for deaf people.

Romero purchased various titles and spliced subtitles between picture frames to accommodate for dialogue, renting them out to deaf schools and clubs. His work thus became the first technique for captioning in film.

His method, however, was considered unsatisfactory because it interrupted the flow of film & dialogue while significantly extending the length of the movie. Copies of his edited film were of poor quality. Lacking funds & support for the movie industry, he abandoned the work.

Edmund Brunke Boatner, superintendent of the American School for the Deaf, was inspired by Romero’s method. Boatner also learned of a Belgium company’s development of etching in films. With C.D. O’Connor, Boater founded non-profit Captioned Films for the Deaf company.

From 1949 to 1958, the company captioned and distributed 29 educational and Hollywood films to deaf schools and clubs across the United States. The CFD board included prestigious Hollywood actors, including Katherine Hepburn.

Captioning became mainstream in 1951 when Warner Brothers produced a captioned version of “America is Beautiful” (1945) The 25min film was meant to sell war bonds.

By 1958, the Captioned Film Act became law and provided federal funding to the CFD to continue open-captioning feature films. Around the same time, Romero began a small business to market alarm clocks and other accessibility tech to deaf people. Emerson Romero died in 1972.

Fun Fact! Emerson is cousin to movie star César Romero (1907‐1994)—known for his role as Joker for TV’s Batman—who likely was influenced by his elder cousin to pursue a career in films.

Further Reading:

Harry Lang & Beth Meath Lang, DEAF PERSONS IN THE ARTS AND SCIENCES (1995)

JE Penn, “Deaf Movie Star,” THE SILENT WORKER (1927) THE BUFF & BLUE (Jan 1935).

Alejandro Oviedo’s biography on Romero.

Leave a reply to LISTEN: CBC q Cancel reply